Countless events have occurred since man began to inhabit this earth, but few of them are relevant enough to deserve to be passed on to future generations. Perhaps this is why so many have undertaken extraordinary measures to accomplish some feat that would give them a share in a much-coveted goal: to appear in the perennial – and selective – pages of that book in which the world writes its memories.

Discoveries, inventions and brilliant works have followed one another, battles have been fought and conquests made… but none of these achievements had the merit of dividing history. It was an apparently unimportant episode unknown to almost everyone at the time, the birth of a Child, which marked humanity for all time. In fact, apart from the Passion, it is impossible to imagine anything so momentous as the birth of Our Lord Jesus Christ, of God who, for love of us and to redeem us, wanted to become Man.

In view of this, it is anything but a futile or insignificant task to define, as far as possible, when was this crucial moment, which St. Paul identifies as “when the time had fully come” (Gal 4:4). And so we invite the reader to enter these complex but most interesting paths, shrouded in a mysterious mist and lost in the darkness of the ages…

The year of the birth of Our Lord Jesus Christ

For us, accustomed as we are to being situated in the twenty-first century after Christ, it is difficult to think of a calendar that does not have the Savior’s birth as its origin. However, this reference point came into common usage little by little during the Middle Ages.

It was only in the sixth century that the monk Dionysius Exiguus – as he liked to call himself out of humility, despite his notable culture – thought of calculating when the Divine Infant had most likely been born. The religious came to the conclusion that Our Lord’s coming took place in the year 753 of the foundation of Rome, and so he made 754 correspond to the year 1 of the Christian era, thereby dispensing with the need to include a “year zero”.

Although it was not immediately known by all, this new way of reckoning time spread throughout Christendom until it became the most widespread and widely used calendar in the world, in preference to other alternatives, such as that of the Jews or the Chinese.

It is a pity that the calculation made by Dionysius was slightly inaccurate, perhaps owing to an error in counting the years of government of an emperor. In fact, the Gospel states that Our Lord was born during the reign of Herod, who had the Holy Innocents killed in order to eliminate the Messiah with them (cf. Lk 1:5; Mt 2:1,13-18). We know, however, that this monarch died in the spring of the year 750 of the foundation of Rome. Therefore, the birth of Jesus must have taken place at least four years before Christ…

A second piece of information provided by the Gospels is that Our Lord came into this world in the time of Caesar Augustus, who ordered a census when Quirinius was ruling Syria (cf. Lk 2:1-2). There is debate among scholars about this detail, but it is perfectly possible to maintain that the census took place between 8 and 6 BC. We hope, therefore, not to disturb the piety of any reader by stating that the most probable date of Our Lord’s birth lies between 8 and 4 BC.1

Why December 25?

The question now arises: what about December 25? Is there any historical reason that justifies the choice of this day for the celebration of Christmas?

The answer is not without its difficulties. First of all, it would seem that the date did not enjoy much importance among the first Christians, since they did not celebrate birthdays. For them, the “dies natalis” – the true nativity – was the day of death, when the person closed his eyes to this life and opened them to Heaven. We find a reflection of this custom in the Liturgy, which, in most cases, celebrates the memorials and feasts of the Saints on the date of their death.

This is, we repeat, in most cases, but not all. There are some births which, because of their excellence, are commemorated in the Church: that of St. John the Baptist, since he was born cleansed of original sin; that of Our Lady, Immaculate from her conception; and, of course, that of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Given the importance of God’s coming to earth for the Catholic religion, the very Gospel of St. John equates the theology of the Incarnation with that of Easter, presenting them as “the two centers of gravity of one faith in Jesus Christ.”2

Moreover, the Church does not celebrate Christmas as a mere remembrance of what happened more than two thousand years ago; it is not an anniversary. Through the Liturgy, the Mystical Body of Christ continues the priestly life of its Head,3 reliving the mysteries that took place then, making them present and being able to share in the same graces received by those who were in the Grotto of Bethlehem, such as Our Lady, St. Joseph or the shepherds. Jesus is born anew every year in the hearts of the faithful.

In any case, although it is difficult to affirm that the feast was not celebrated in some way since the beginning of Christianity, references to December 25 as the date of the Solemnity of Christmas are rather scarce until the fourth century, and present historians with some difficulty.4 In the absence of documents, hypotheses began to emerge.

The theory of the feast of “Sol Invictus”

A widespread explanation is that this date corresponded to a pagan celebration that existed in Rome: the day of the Sol Invictus, instituted by the Emperor Aurelianus in 274 AD. The Nativity of Our Lord, the true “Sun of Justice” (Mal 4:2), would have been assimilated to the feast of the false god, in order to eliminate it.5

This theory, however, does not satisfy everyone for several reasons. Analyzing the psychology of the Christians of that period, it is worth asking: would they contaminate such a sublime feast by assimilating it to a pagan festival? Having just been persecuted by the Romans and preferring to spill their blood rather than burn a little incense to idols, would they consent to take such a date for the Solemnity of Christmas? These and other motives have led authors such as Cardinal Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, to affirm that “today the ancient theories according to which the 25th of December arose in Rome in opposition to the myth of Mithras, or also as a Christian reaction to the cult of the Sol Invictus, are untenable.”6 In the work we have quoted, the then Cardinal preferred to defend another theory,7 perhaps the most poetic and theological of all.

The perfection of symbolism

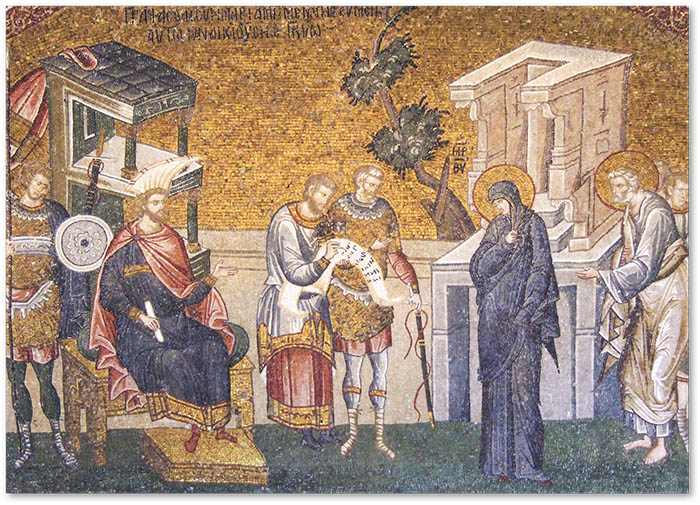

of Art, Detroit (MI)

This hypothesis is based on the symbolism and interpretation of numbers. According to an ancient tradition, the creation of the world began on March 25, a date that the first Christians thought should coincide with the new creation, that is, the death of Our Lord on Calvary. Now, in their reckoning, it was fitting that Christ should spend an exact number of years on this earth. Therefore, not only His Passion, but also His conception should have taken place on March 25. Adding to that the nine months of gestation – equally precise, since Mary’s pregnancy was perfect – the conclusion was reached that Christmas would have occurred on December 25.

Arguing that this tradition was widespread among the faithful even before the rise of the Emperor Aurelian, Ratzinger and the other authors who share the same opinion call into question the theory of the Sol Invictus.

However, historically, is that enough for us to affirm with complete certainty that Jesus Christ was born on December 25? Perhaps we need more information.

The conception of St. John the Baptist

Another current calculates the period in which the Saviour was born on the basis of the Gospels. The four hagiographers, however, do not suggest any specific date for the advent of the Messiah. What we know from their writings is that at the sublime moment of the Annunciation to Our Lady – and consequently of her virginal conception – the Archangel Gabriel mentioned the state of her cousin Elizabeth. She had conceived a child, and it was already the sixth month for her that everyone considered barren (cf. Lk 1:36). In nine months’ time, the Saviour would be born.

Now, if we calculate the period that goes from the conception of St. John the Baptist – six months before the Annunciation – to the Nativity of Our Lord – nine months after the Annunciation – we obtain the sum of fifteen months. In other words, the Precursor was conceived one year and three months before Jesus was born. If we can find out the exact date on which Elizabeth became pregnant, it will be easy to define the date of Christ’s birth. However, how can we find the day of the Baptist’s conception?

Although Elizabeth and her husband desired offspring, this was made impossible by their sterility and advanced age. But one day, when Zechariah was “serving as priest before God when his division was on duty, according to the custom of the priesthood, it fell to him by lot to enter the Temple of the Lord and burn incense” (Lk 1:8-9). On that occasion, the Angel of the Lord appeared to him to tell him that the supplications of the two had been answered: his wife would bear a son.

It is known that the priests took turns serving the Temple in groups twice a year. Zechariah belonged to the eighth shift, that of Abijah (cf. Lk 1:5). According to an ancient Christian tradition which dates back to at least the second century, he exercised his priestly functions during the Jewish festival of Yom Kippur, the day of atonement, which was celebrated at the end of September. Add to that fifteen months, and we arrive at the last days of December, when Our Lord would have been born. Among the staunchest defenders of this thesis is St. John Chrysostom,8 Patriarch of Constantinople, who used the same argumentation to establish Christmas on the 25th, as we still celebrate it today.9

Christmas in the Liturgy

It is clear that, twenty centuries after these events, trying to define the date of Christmas in an indisputable way becomes a very difficult task, if not an impossible one. We can hope that this will be one of the many questions that we will be able to ask when, by God’s mercy, we reach Heaven and beseech Our Lady to tell us a little of the history surrounding those wonderful and mysterious days when the “Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (Jn 1:14).

For the moment we must limit ourselves to savouring the crumbs that time has not devoured, in order to identify, to the degree possible, the origin of this solemnity which, together with Easter, constitutes the principal feast of the true Religion.

Nevertheless, much more than a simple historical reality, the celebration of Christmas on December 25 contains a profound theological reality. Providence willed that it be celebrated during the period when, in the northern hemisphere, the winter solstice occurs – the day of the year when night is longest – in order to better reflect God’s way of acting in history.

At a time when the darkness of sin and death seemed to dominate the entire universe and the power of darkness was about to suffocate the day, Our Lord Jesus Christ was born, the “Light of the world” (Jn 8:12), who shines in the darkness and whom darkness cannot overcome (cf. Jn 1:5). That night a sentence of extermination was decreed against the empire of the Serpent, driven to retreat by the overpowering rays of the Sun of Justice. Thus, at Christmas, the Divine Infant began the most beautiful of all re-conquests: the Redemption of the human race which – through disobedience – had become enslaved to sin.

This is how God acts in history. When evil seems to be winning, it is an unequivocal sign that its end is near, for the hour of divine intervention has arrived. ◊

Taken from the Heralds of the Gospel magazine, #182.

Notes

1 Cf. DI BERARDINO, Angelo (Dir.). Patrología. Madrid: BAC, 2000, v.IV, p. 237-239; LEAL, SJ, Juan; PÁRAMO, SJ, Severiano; ALONSO, SJ, José. La Sagrada Escritura. Evangelios. Madrid: BAC, 1964, v.I, p.570-571.

2 RATZINGER, Joseph. El espíritu de la Liturgia. Una introducción. Madrid: Cristiandad, 2001, p.129.

3 Cf. PIUS XII. Mediator Dei, n.2-3.

4 The oldest reference to December 25 that has come down to us is from St. Hippolytus (cf. Commentaire sur Daniel, IV, 23: SC 14, 307), in a work written between 202 and 204. However, many authors dispute the authenticity of the passage in which the date is mentioned.

5 Cf. RIGHETTI, Mario. Historia de la Liturgia. 2.ed. Madrid: BAC, 1955, v.I, p.689.

6 RATZINGER, op. cit., p.130.

7 Cf. Idem, p.131-133. See also: BRADSHAW, Paul. La Liturgie chrétienne en ses origines. Paris: Du Cerf, 1995, p.227-229.

8 Cf. ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM. Homilia in diem natalem Domini Nostri Jesu Christi, n.4: PG 49, 356-358.

9 Based on the Qumran findings, some scholars have corroborated that the second week of service of Abijah’s watch occurred in late September (cf. FEDERICI, Tommaso. 25 dicembre, una data storica. In: www.30giorni.it).