For this exemplary girl of spirited temperament and abundant natural qualities, the matrimonial path seemed to be the one by which she would reach sainthood. However, God had loftier designs for Humbeline…

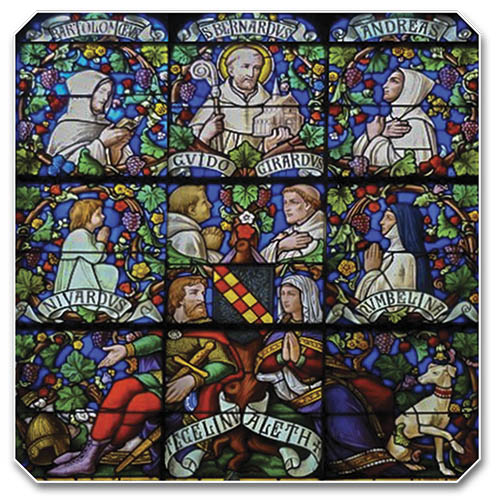

In the long-ago 12th century, in Burgundy, France, there lived a noble family made up of Tescelin, lord of Fontaines, his wife, the pious Aléthe, and their seven children: Guy, Gerard, Bernard – who would become the great abbot of Clairvaux –, Humbeline, André, Barthélémy and Nivard.

In the castle where this blessed offspring came into the world, harmony and the religious spirit proper to the Middle Ages reigned among all; mutual encouragement to the practice of virtue was their daily bread. They talked about the Creator with all naturalness, and fidelity to the Commandments was the norm. The duties that the Holy Church entrusted to Catholic warriors – to defend it and to love one another – were valiantly fulfilled by Tescelin, whose example his children soon began to imitate.

In the midst of a society that regarded chivalry as the best expression of a man’s moral virtues, the six boys of the family possessed all the attributes to become famous and successful figures. And for Humbeline, the only girl among these siblings, the future also looked bright. Gifted with an uncommon beauty, sweetness and fortitude, gentleness and intrepidity were united in her, and there would be no lack of suitors on a par with her dignity.

It was easy to foresee a brilliant future awaiting each of the members of this family. What no one could have imagined was that they would shine in history with a glory far greater than that won by human qualities, however high, and would come down through the ages exalted by the Church with the honor of the altars.

An exemplary mother

Known throughout the duchy for her profound unpretentiousness and generosity towards those in need, Aléthe of Montbard formed the solid foundation of her children’s holiness. Of a firm and kindly character, she instilled in their hearts not only a horror of sin but also generosity towards God, to such an extent that all of her sons were able to renounce one good – chivalry – in order to embrace a greater one: the vocation to which Providence had destined them, in religious life.

“I cannot forget,” writes one of St. Bernard’s friends, “how this illustrious lady sought to serve as an example and model for her children. Being at home, married and in the middle of the world, she imitated in some way the solitary and religious life, by her abstinence, by the simplicity of her clothing, by her detachment from the pleasures and pomp of the world; she withdrew whenever possible from the agitations of worldly life; persevering in fasting, vigils, and prayer, and compensating by works of charity for what might be lacking in the perfection of a person committed to marriage and engaged with the world.”1

A fervent devotee of St. Ambrose, Aléthe died on the feast of this Doctor of the Church in 1110, after receiving Viaticum and the Anointing of the Sick. Just before she passed away, she asked those present to recite the Litany of All Saints. While they recited the aspiration “Through your Cross and Passion, deliver us, Lord,” she sat up, made the sign of the Cross with profound reverence, raised her arms to Heaven and then reclined serenely, entrusting her soul to God.

It is said that of all the children, the one who felt the death of his mother the most was young Bernard, then nineteen years old. Attentive to the voice of grace, Aléthe had well understood that he was specially called by Providence, and she paid particular attention to his formation.

The fruits of this genuine maternal affection soon came to light in an excellent way: at the age of twenty-one, Bernard decided to become a monk of the Cistercian Order, a reformed branch of the Benedictines, then in its infancy and devoid of prestige in the eyes of the world. Many family members, including his sister, were disconcerted by his decision, but this did not constitute the slightest obstacle for him. If such was the will of God, nothing would make him turn back.

And Bernard would not go alone: having encouraged his brothers one by one to give themselves completely to God, they all followed him. The father himself would end his days as a lay brother in the community of Clairvaux.

The last to leave the world to embrace the ways of perfection was Humbeline, thus completing the “crown of seven heavenly stars that the mother of St. Bernard wears in the Kingdom of Heaven.”2

Lady of fiery character, molded by virtue

Humbeline had a spirited temperament, which her parents were able to mold into a holy fear of God. It is said that she rode skillfully and took part in daring hunts with her father and brothers. She crossed briers and thorns, and when she fell, she got up with the agility and nonchalance of a warrior. Her beauty reflected the purity of her soul, in which shone the fundamental virtue of humility, which enhances every quality or gift.

As all the brothers became religious, the family properties and fortune accumulated in the hands of the young Humbeline. Shortly thereafter, she married Guy de Marcy, nephew of the Duke of Burgundy. Although she had approached married life seriously, she was soon absorbed by the vanities of the world, indulging in frivolous amusements and pastimes and seeking to make the most of the luxury and pomp that her status afforded her.

A visit to Clairvaux

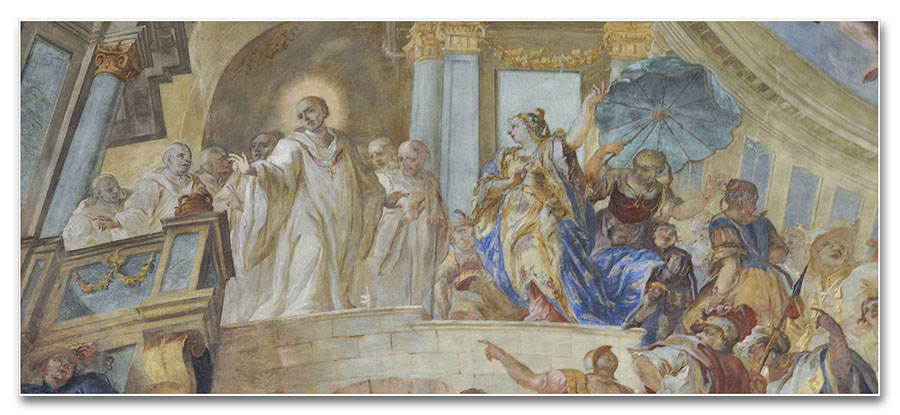

One day, keenly missing her beloved brother Bernard, Humbeline went to visit him at the Monastery of Clairvaux, of which he was abbot. She was received by another of her brothers, André, who was doorkeeper at the time. On seeing his sister decked out in ostentatious finery, accompanied by a showy retinue, the young religious could not hide his astonishment and disapproval. He asked her to wait while he went to inform the abbot of the visitor who was waiting for him.

A few moments later André returned with a message that caused Humbeline to burst into tears: Bernard would not receive her. Understanding that her brother’s contempt was due to the excesses of luxury with which she presented herself – a sign that she had given in to the illusions of the devil – she recognized her deplorable spiritual state and insisted with André: “I am a sinner, but Christ died for sinners. It is because I am bad that I seek the company and counsel of the good. If my brother does not esteem his own blood, let him at least not despise or forsake my soul. Let him come and see me, and command me to do whatever he pleases, for I am ready to do whatever he sees fit.”3

The holy abbot, hearing of Humbeline’s good reaction, was filled with compassion and sent for all the other brothers to come see her. With the firmness and gentleness proper to him, the Mellifluous Doctor reminded her of the example of her virtuous mother, persuading her that sanctity was not incompatible with marriage. And he exhorted her: “Is it possible that only you, among so many siblings, will be slave of your body, while they are concerned only with the health of their soul? So many longing for Heaven, and only you buried in the earth? So many thinking each instant about death, and you as if you were to remain forever in the world? Will your judgement prevail, and will you alone glory in the rottenness which will serve as food for the worms, and will you live forever forgetful of the good and usefulness of your soul? What payment will you make, in the next life, for these fleeting pleasures, this momentary glory and such superfluous expenditure?”4

They talked at length… Humbeline felt herself cleansed in fresh, perfumed water. She understood that true happiness can only be found in God and that all the riches of the earth could never quench her thirst for the infinite.

When the magnificent retinue left Clairvaux, Humbeline had made an important decision.

A sudden and complete change

Back at the Castle of Fontaines, Humbeline began a new life: abandoning all excesses of luxury, she began to follow a routine marked by austerities, with mortifications and long periods dedicated to prayer.

After two years, she asked her husband for permission to retire to a convent, for she clearly felt the voice of grace calling her to a life of total renunciation of all that was earthly, and of continuous holocaust in praise of God. Although they had no children yet, it was not easy for Guy to agree. Only when he had thought it over and made sure that it was God’s will did he give his consent, and immediately felt a deep joy in his soul.

Having settled the matrimonial question according to the discipline of the Church, she finally entered the Benedictine convent of Jully-sur-Sarce, of which Elizabeth de Forez, her sister-in-law, was abbess.

Humbeline took great strides on the road to sanctity; demonstrating exemplary obedience, radical austerity and constant humility. She performed the lowliest tasks with simplicity, wishing in this way to atone for the worldly life she had led. She spent many nights in continuous prayer, meditating on the sorrowful Passion of Our Lord.

She was surprised to be unanimously elected prioress of the convent when Elizabeth was sent to direct a new house. In this office, she was so successful in transmitting the fortitude and gentleness of her Spouse, Jesus Christ, that some have called her the feminine version of the great Abbot of Clairvaux.

Joyful even in death!

The joy of the Saints is evident even in death. On reaching the age of fifty, of which sixteen years had been spent in religious life and about eleven as abbess, Humbeline felt her strength beginning to wane. On being informed of the failing health of his sister, already bedridden, St. Bernard went to Jully in the company of André and Nivard.

It was Humbeline’s greatest desire to be with Bernard, and it was enough to hear his voice for her to recover her strength and begin a pleasant conversation with her three brothers. She declared how happy she was to have followed Bernard’s advice, telling him: “The best life, which is that of my soul, I owe to your persuasion and doctrine; now I pray you proceed and free me, as I hope, from eternal punishment.”5

After a brief visit, during which she appeared happy and cheerful, the brothers decided to leave her and retire to the convent hostel. A few moments later, however, an angel appeared to Humbeline’s confessor, who was also there, and warned him that she was about to expire. Then the floorboards began to creak without anyone touching them, and as everyone in the monastery rushed to see what was happening, the priest warned them of the abbess’ imminent death.

They rushed to her bedside, and she, smiling, greeted each one of those who arrived, and then she proclaimed the psalm: “Lætatus sum in his quæ dicta sunt mihi: in domum Domini ibimus” (122:1).6 Her face was illuminated by a heavenly radiance. After a few moments, she fixed her gaze on Heaven and with ineffable serenity she entrusted her soul to God. It was August 21, 1141.

According to some, her body exuded a strong fragrance that consoled everyone around her, and her beautiful face belied the illness she had suffered.

“To love is to serve”

If we wish to sum up Bl. Humbeline’s life in a few words, we need to look no further than the motto that she herself adopted: “To love is to serve”. It is said that this phrase was sent to her by St. Bernard, written on a small parchment, in reply to a letter in which his sister complained about the number of her responsibilities, which left her almost no time for meditation.

She considered these few words as valuable as a long treatise, because they pointed out the ideal for which she lived, the reason why she should always give of herself, fighting fatigue without discouragement, feeling irritated without showing it and continuing to desire solitude without ever having a moment to herself.

As one author well expressed it, this phrase made the voice of her dear brother Bernard resound in our Saint’s heart, as if constantly repeating to her: “Humbeline, our Beloved is a zealous lover who does not tolerate haggling over sacrifice. Work for Him even unto death, and do it smiling!”7 ◊

Article taken from the Heralds of the Gospel Magazine, #172.

1 D’HÉRICAULT, Charles. Les mères des Saints. 2.ed. Paris: Gaume et Cie, 1985, p.124-125.

2 Idem, p.134.

3 MUÑIZ, O. Cist, Roberto. Medula historica cisterciense. Valladolid: Imprenta de la Viuda de D. Tomás de Santander, 1785, t.IV, p.4.

4 Idem, p.5.

5 Idem, p.8-9.

6 From the Latin: “I was glad when they said to me, ‘Let us go to the house of the Lord!’”

7 RAYMOND, OCSO, M. La familia que alcanzó a Cristo. Barcelona: Herder, 2003, p.231.