We will never understand the spirituality of St. Anthony of Padua without viewing it from an essential and ever-present aspect of existence in this valley of tears: struggle, combat and suffering.

It was the year 1221. In the austere Franciscan convent of Forli, Italy, some sons of St. Francis and St. Dominic had gathered for a liturgical celebration, during which several religious received the Sacrament of Holy Orders. At the end of the ceremony, the Provincial of the Friars Minor asked that a Preaching Brother proffer the closing words. All declined the honour since no one had prepared a speech and improvisation can be risky on solemn occasions…

To solve the quandary, the Franciscan Provincial confided in the inspiration of grace and assigned the duty to one of his subordinates. He appointed a Portuguese friar to the task—a kitchen aid from the Hermitage of St. Paul. With the simplicity of souls accustomed to obedience, the humble religious, silent until then, set about fulfilling the order. To the surprise of all he did so in fluent Latin.

As he overcame his initial timidity, the words of the brother, based on Scripture, grew in lustre, passion and clarity. When he finished, the fact that he was a modest cook had vanished from the minds of his listeners. He had been transformed in their presence into an outstanding preacher.

The public life of St. Anthony of Padua had begun. The struggle against self and against evil, waged until then in the solitude and austerity of the cloister, at that moment took on a missionary dimension. God had convoked him to evangelize the multitudes, to aid them, through the ministry of the word, in the ongoing and uncompromising fight against sin.

Fight? Perhaps this word will strike a discordant note with those who envision this saint according to the smiling images that portray him as a man brimming with joy, sweetness and consolation. But the struggle against one’s own defects and against evil is the inseparable companion of the homo viator, in consequence of original sin. A saint’s spirituality cannot be understood without viewing it from this essential and ever-present aspect of existence in this valley of tears: struggle, combat and suffering.

In the footsteps of St. Augustine

Not half a century had elapsed since the reconquest of the Portuguese capital by King Afonso Henriques, when around the year 1193 Fernando Martins was born there, the future St. Anthony of Padua… or, “Anthony of Lisbon,” according to the Portuguese, who take warranted pride in their illustrious compatriot.

Having clearly heard the call of God to religious life, at age fifteen he entered the Order of Canons Regular of St. Augustine, in the Monastery of St. Vincent Outside the Walls, built in thanksgiving for the taking of the city. He embraced this decision not to flee from his military obligations as a noble, but rather to perfect himself in the fight against the world, the flesh and the devil, for as Montalembert affirms, “Contrary to being a refuge for the weak, convents were the arena of the strong.”1

Two and a half years later, his superiors authorized his transfer to the Monastery of the Holy Cross in Coimbra, affording him further seclusion from the world—the chief opponent of virtue—and detachment from personal ties. In the new dwelling, situated in the intellectual hub of the fledgling country, Fernando imbibed the doctrines and teachings of the author of the Rule, St. Augustine, and other Fathers of the Church. He also acquired a vast knowledge of Sacred Scripture, the foundation for his future preaching. It was in this city too that he was elevated to the priestly rank.

Franciscan vocation

A new breath of the Holy Spirit was awakened in the Church at that time. In opposition to the unbridled luxury and attachment to material goods that had begun deviating the spirit of faith that characterized medieval man, illustrious figures such as Dominic of Guzman and Francis of Assisi emerged to admonish the evils of the age by word and example, inviting Christians to reanimate their fervour through the practice of poverty.

The zeal transmitted by the Seraph of Assisi to the Order of Friars Minor was such that, only eleven years after the foundation, five of St. Francis’ sons died as martyrs in North Africa. The courageous missionary endeavours of these indomitable religious in preaching the Faith of Christ had raised the ire of the caliph of Morocco who ordered their execution.

In the middle of 1220, the mortal remains of these heroes of the Faith arrived in Coimbra amidst great pomp, and were exposed for the veneration of the faithful in the Monastery of the Holy Cross chapel. Canon Fernando took this as a sign of Heaven’s approval of his desire to join the sons of St. Francis whom he greatly admired, in the Convent of St. Anthony of Olivares.

In due time, having obtained leave from his superiors, Canon Fernando received the habit of the Friars Minor, taking the name of Friar Anthony. Dressed in a rustic garb, the brilliant priest from Lisbon sacrificed his prestige, opulence and culture with no regrets.

Renunciation of self-will

After only five months into the novitiate he succeeded in being sent to the land that had produced the first martyrs of the Franciscan Order. He thought he had reached the height of his earthly conflict and eagerly awaited the palm of martyrdom. But Providence wanted a more protracted struggle from him, the first step of which consisted in the total renunciation of his own will. Shortly after disembarking on African soil, he was laid low by a fever which reduced him to inactivity. The superior sent him back to Europe.

On the return trip, a storm grounded the ship on the shores of Sicily. After spending some months in the convent of Messina, Friar Anthony set out for Assisi, where the General Chapter of the Order was held on the eve of Pentecost 1221, presided by St. Francis himself.

After the Assembly had closed, and still a stranger in that multitude of friars, he requested that the Provincial of Romandiola accept him as a subordinate. With this, his life in Hermitage of St. Paul began. With a blind eye to his lineage and formation he was assigned the task of kitchen helper, which he accepted without a murmur. He spent many months in anonymity; his cell was a cave, and he accepted everything without complaint. Who could say that this victory over self was of lesser value than that of the martyrs of Morocco?

It was during this period of humiliation and anonymity that the episode regarding the ordination ceremony in Forli, narrated at the beginning, took place.

Dauntless preacher

“We must not remain silent before evil.”2 These words of Pope Benedict XVI could well sum up the preaching of our saint. Gifted with devotion, eloquence and an exceptional memory—he knew the Scriptures by heart—Friar Anthony attracted multitudes by his preaching. He fearlessly admonished the errors of his listeners, even when they were civil or ecclesiastical authorities.

He once publicly upbraided a bishop who was given to vain attire: “And as for you, there, in the mitre!”3 He censured the prelate for his faults, and the bishop, acknowledging his guilt, shed copious tears and changed his ways. He also sought out the cruel governor Ezzelino in Verona, and confronted him there.

Unanimous in recognizing the deep theological content of Friar Anthony’s sermons as well as his saintly conduct, the friars asked St. Francis to assign him to teaching them sacred doctrine. Until then, the holy founder had shown himself ill-disposed to Franciscans dedicating themselves to study, fearing that this might deviate them from the charism of the Order and lead to spiritual laxity. But, aware of the virtues of his spiritual son, he acceded to the friars’ request, writing to the saint: “I am pleased that you teach sacred theology to the brothers providing that, as is contained in the Rule you “do not extinguish the Spirit of prayer and devotion during study of this kind.”4

Mission in France influenced by heresy

His teaching position with his brothers was of short duration, since the holy religious was sent, in 1224, to preach in southern France then beset by the Cathar (or Albigensian) heresy. For three years he traversed the cities of Montpellier, Toulouse, Le Puy and Limoges, bringing the light of the true Faith. He received expressions of sincere repentance from many of his listeners; and from others, contempt and mockery, despite the fact that his preaching was accompanied by numerous miracles.

For example, a Cathar in Toulouse who persisted in denying the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist put him a challenge: a mule would be left for three days without feed, and then it would be brought to the public square, where Friar Anthony would present it with the monstrance with the Blessed Sacrament, and the heretic with a bale of hay. The challenge was carried out. When the famished animal entered the square he first made a deep reverence to Jesus in the Eucharist before touching the food. Many witnesses converted because of this remarkable miracle.

Fidelity to Franciscan charism

In 1227, Friar Anthony definitively left France. During the first General Chapter of the Order after the death of the Seraphic founder, he was elected Minister Provincial of Emilia-Romagna, a region of northern Italy, where he would dedicate the last four years of his life.

The city of Padua, seat of the Provincialate, was the recipient of many of the saint’s words, examples, and displays of kindness. With untiring diligence he also visited Ferrara, Bologna, Florence, Cremona, Bergamo, Brescia and Trent, opening new convents, presiding over ceremonies of imposition of habits—always and ever being a model of holy poverty. God had withdrawn the Poverello from the world, but had left a “second Francis” with the task of fighting to preserve the flame of his work.

The effect of his holiness was not limited to the ambit of the Friars Minor, but encompassed the entire population. Churches could not contain the crowds—sometimes numbering twenty thousand—that flocked to hear him. After listening to one of his Lenten sermons, Pope Gregory IX called him the “Ark of the Testament” and the “Repository of Holy Scripture.”5

This intensity of activity was interspersed with periods of recollection, in which he recovered, in contemplation, the strength for action. His favourite place for prayer was the holy Mount Alverne, where his holy founder had received the sacred stigmata—an awe-inspiring setting that favoured contact with the supernatural. He spent the winter of 1228 there.

“I have fought the good fight”

His preaching during Lent of 1231 was particularly well attended as his renown for eloquence and holiness had spread far and wide. But prestige did not perturb his well-grounded humility. It was his habit to go from pulpit to confessional, where, with unflagging zeal, he reaped the fruits of preaching.

But the weight of his labours eventually undermined his health. The many trips undertaken with an evangelical spirit, shod only in Franciscan sandals were debilitating. Struck by a case of edema, he withdrew for a period of repose in the small community of Camposampiero. In the woods on the grounds there was a gigantic walnut tree, and there he established a small cell for himself. In this unique setting he attended the faithful who came to him.

One day, feeling especially low, he asked to be taken to Padua, to avoid being a burden on the small community. However, during the journey, his state suddenly worsened and, although he was close to his destination, he had to stop at the monastery of the Clarists of Arcella.

Feeling his end approaching, Friar Anthony steeled his soul for the final battle, filled with confidence in Mary, to whom he was ardently devoted and who had always fortified his enthusiasm during this earthly pilgrimage. After confessing and receiving Extreme Unction, he intoned his favourite hymn, “O Gloriosa Domina, excelsa super sidera…”—O Heaven’s Glorious Mistress,enthron’d above the starry sky! During his final agony his eyes became fixed on the heavens and he exclaimed: “I see my Lord.”6 Shortly afterwards, his spirit took flight to the Most High to receive the crown of glory that awaited him.

Like St. Paul, he could exclaim: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith. Henceforth there is laid up for me the crown of righteousness” (2 Tim 4: 7-8). It was June 13, 1231; Friar Anthony was not yet 40 years old.

* * *

The heavenly reward was soon confirmed on earth: less than a year after his death, on May 30 of the following year, he was canonized by Pope Gregory IX, enabling the Church to solemnly celebrate the first anniversary of his death. And in 1263, during the transferral of his relics to the Basilica built in his honour in Padua, St. Bonaventure, then General of the Order, found the tongue of the saint to be intact. Time did not dare disfigure that victorious instrument of battle that had freed so many souls from the clutches of sin! ◊

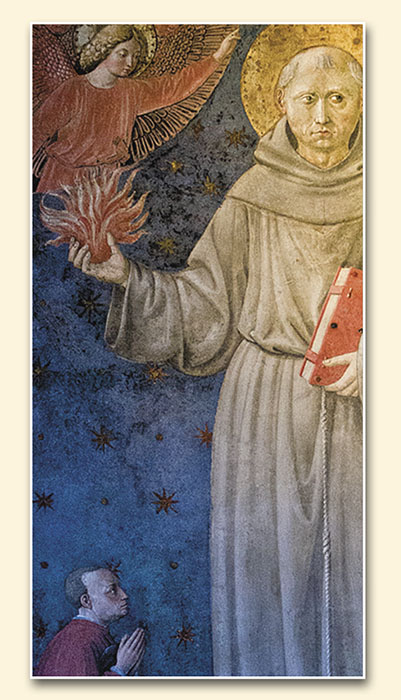

The Fire of the Holy Spirit

An excerpt from one of St. Anthony of Padua’s sermons reveals the ardour and theological depth of the preaching of the “Doctor Evangelicus.”

What material fire does to iron, this fire does to the wicked, cold and hard heart. At the incoming of this fire, the human mind little by little loses all its blackness, coldness and hardness, and wholly takes on the likeness of that by which it is inflamed. For this purpose it is given to man, for this it is breathed into him, that as far as possible he may be configured to it. For, from the burning of the divine fire, he becomes completely white-hot, and blazes forth equally, and melts into the love of God, according to these words of the Apostle: “God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us (Rom 5:5).”

Note that by burning, fire brings low what is high, joins together what is divided (as iron to iron), makes bright what is dark, penetrates what is hard, is always mobile, directs all its movements upwards, fleeing the earth, and enveloping into its own proper operation whatever it invades.

These seven properties of fire can be referred to the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, which, by the gift of fear, brings low what is high—that is, proud; by the gift of piety, joins divided and separated hearts; by the gift of knowledge, makes bright what is dark; by the gift of fortitude, penetrates hard hearts; by the gift of counsel, is always in motion—for he who is counselled by this inspiration does not remain idle, but moves promptly toward his own salvation and that of others, for the grace of the Holy Spirit is not akin to slow and tardy efforts; by the gift of understanding, He influences all man’s movements, because by his inspiration He gives man to understand—that is, to read the interior, to read the heart—that he may seek what is heavenly and flee what is earthly; by the gift of wisdom, He transforms the mind in which He is infused to his own operation, because He gives it a taste for things of the spirit. Ecclesiasticus says: “I perfumed my dwelling” (24:21).

(Excerpts from Sermon 76 – On the Feast of Pentecost)

Taken from the Heralds of the Gospel magazine, #56.

1 MONTALEMBERT, apud RÖWER, Basílio. Santo Antônio: vida, milagres, culto. 4.ed. Vozes: Petrópolis, 1968, p.16.

2 BENEDICT XVI. Message for Lent 2012, from 3/11/2011.

3 NIGG, Walter. Antônio de Pádua. São Paulo: Loyola, 1983, p.36.

4 Idem, p.44.

5 GREGORY IX, apud PIUS XII. Litteræ Apostolicæ Exulta, Lusitania Felix, 16/1/1946.

6 RÖWER, op. cit., p.98.