“There was once a time when States were governed by the philosophy of the Gospel. Then it was that the power and divine virtue of Christian wisdom had diffused itself throughout the laws, institutions, and morals of the people, permeating all ranks and relations of civil society. Then, too, the religion instituted by Jesus Christ, established firmly in befitting dignity, flourished everywhere, by the favor of princes and the legitimate protection of magistrates; and Church and State were happily united in concord and friendly interchange of good offices. The State, constituted in this wise, bore fruits important beyond all expectation, whose remembrance is still, and always will be, in renown, witnessed to as they are by countless proofs which can never be blotted out or ever obscured by any craft of any enemies.”1

With these luminous words, Leo XIII paid homage to the Middle Ages, that historical epoch whose apex could be said to represent a true springtime for the Christian Faith, reflected both in the religious and in the civil sphere of society. Undoubtedly, one of the “fruits, important beyond all expectation,” to which the celebrated Pontiff refers, is theology.

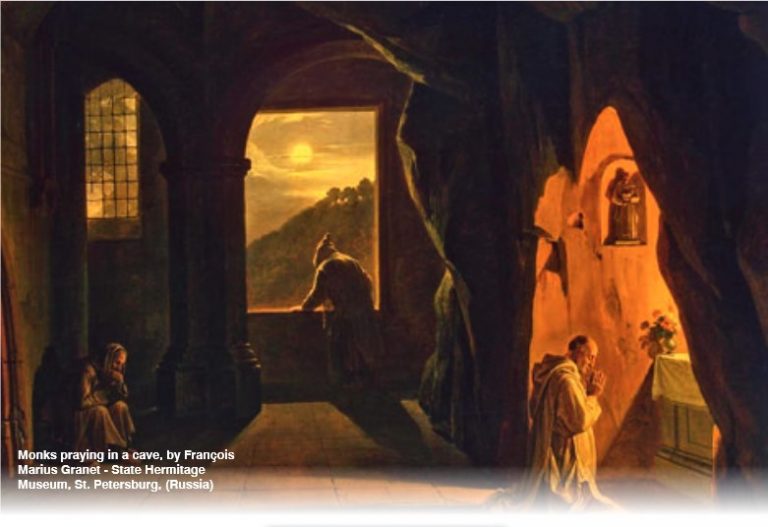

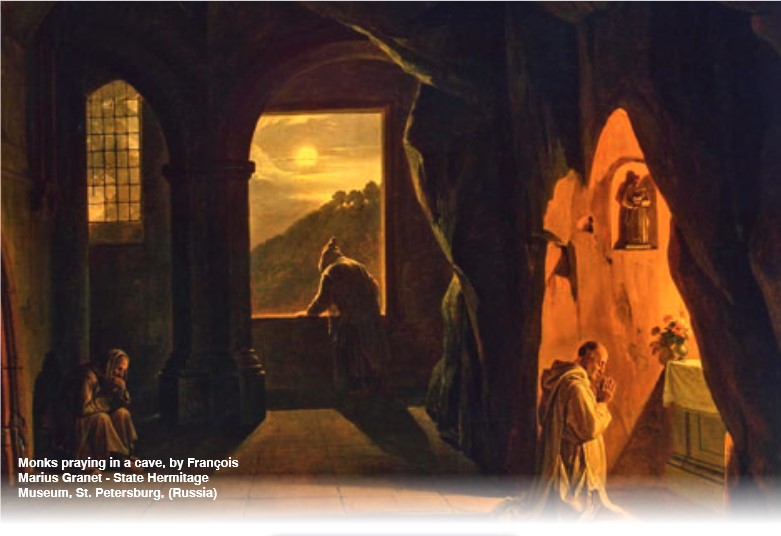

A “theology on bent knee”

“Theology on bent knee,”2 an apt expression of a theologian Pope, Benedict XVI, points to a theology born of love, piety, and contemplation of God and His mysteries, while, at the same time, of an intimate union between faith and reason.

It would be a mistake to believe that medieval theologians lived sealed off in libraries, racking their brains, endlessly formulating abstractions to fuel their theological arguments and speculations, disconnected from the realities of life. On the contrary, their theology flowed, like a torrential river, from an interior life joined with reflection.

This apt expression of a theologian Pope, Benedict XVI,

points to a theology born of love, piety, and

contemplation of God

This theology, called “monastic theology”, a product of the High Middle Ages, born amidst the shadows—or, rather, the light—of the abbeys and monasteries, to which not only religious, but also the laity repaired to study Sacred Scripture. It was actually an extension of the lectio divina which had its place between the chanting of the psalms, reflection on the Word of God and the teachings of the Holy Fathers. “The master sought to fill the soul of his disciples with the fruit of his spiritual experience, building a theology not as a science in the strict sense, according to the standards of Aristotelian dialectic, but as a science of the heart.”3

The true progress of this era is rooted in the impetus received from various concomitant factors. The first of these was the initiative of the Emperor Charlemagne and his counselor, Alcuin of York. The latter, an English monk, who directed the palatine school, was remarkable for his intellectual activity, and wrote various theological tracts. Other factors were the immense spiritual benefits gained from the Gregorian reform and from the expansion of Cluny, whose abbot, St. Odo, spread not only the rule of St. Benedict, but also what could be called the “monastic spirit”, yielding fruits of holiness and liturgical splendor. This in turn sparked in all of Europe an appetite for deeper studies in the knowledge of God. However, the soul of all these factors was a “breath” of grace from the Holy Spirit which swept across Europe.

Monastic theology and scholastic theology

There were still no universities, and theological studies took place in two settings: the monasteries and the scholæ, that is, the schools of the city. Hence the distinction between “monastic theology” and “scholastic theology”, like two trunks of the same tree.

Monastic theology, developed by fervent monks in cloisters, was essentially aimed at cultivating the love of God and the desire for heavenly things in souls. It can therefore be described as “meditation, prayer, a song of praise and impels us to sincere conversion. On this path, many exponents of monastic theology attained the highest goals of mystic experience.”4

Scholastic theology, in its turn, “was practiced at the scholæ which came into being beside the great cathedrals of that time for the formation of the clergy, or around a teacher of theology and his disciples, to train professionals of culture in a period in which the appreciation of knowledge was constantly growing.”5

The study method of the scholastics was the quæstio, that is, the problem presented to the reader’s mind while analyzing the words of Scripture and of Tradition. The formulation of this problem elicited questions and gave rise to discussion between master and students, the disputation. In these debates, themes of authority arose, alongside those of reason. In this way, the debate was directed toward establishing concord between authority and reason. The organization of the quæstiones led to the emergence of the summæ, which in reality were weighty theological dogmatic treatises sprung from the confrontation between human reason and the Word of God.

Dialogue between faith and reason

This is where the perennial lesson of monastic theology is introduced. Faith and reason, in reciprocal dialogue, tremble with joy when both are animated by the search for intimate union with God. “When love enlivens the prayerful dimension of theology, knowledge, acquired by reason, is broadened. […] knowledge only grows if one loves truth. Love becomes intelligence and authentic theology, wisdom of the heart.”6

These enlightening words of Benedict XVI make it easy to understand how the theology which flourished in the eleventh and twelfth centuries prepared the way for the so-called “golden age of Scholasticism” in the thirteenth century. During this period, St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Bonaventure, among others, shone with special brilliance.

Many volumes would be necessary to provide an accurate picture of the great theologian saints who arose in the monasteries of the High Middle Ages. Therefore, we limit ourselves here to providing an overview, à vol d’oiseau, of two of its greatest exponents, who marked the history of the Church and theology for all time: St. Anselm of Canterbury and St. Bernard of Clairvaux.

Excerpt from the Heralds of the Gospel magazine, #95

Notes

1 LEO XIII. Immortale Dei, n.21.

2 BENEDICT XVI. Address in the Abbey of Heiligenkreuz, 9/9/2007.

3 ILLANES, José Luis; SARANYANA, Josep Ignasi. Historia de la teología. Madrid: BAC, 1995, p.5.

4 BENEDICT XVI. Monastic Theology and Scholastic Theology. General Audience, 28/10/2009.

5 Idem, ibidem.

6 Idem, ibidem.