What wisdom resounds in the words of Cicero, when he defines history as the “evidence of time, the light of truth, the life of memory, the directress of life, the herald of antiquity”!1 These words are especially true of great personages, but above all of those who were saints, for the memory of the path of virtue they trod in the past illuminates the present and projects a light into the future.

A continuous line of prophetic Marian devotion

Elijah, the Thesbite, is one such emblematic figure. Born in the year 900 B.C., he “enters suddenly upon the history of the Kingdom of Israel, with prodigious brilliance: ‘Then the prophet Elijah arose like a fire, and his words burned like a torch’”(Sir 48:1).2

Having consumed his existence, having been “very jealous for the Lord, the God of hosts” (1 Kgs 19:14), he anointed Elisha as his successor, and was then swept up by a “chariot of fire and horses of fire” and ascended “by a whirlwind into heaven” (2 Kgs 2:11). He “lives on, according to the holy tradition of the Catholic Church,”3 and before the second coming of Christ, “on the cusp of the great and terrible final Judgement, Elijah will return.”4

Among his extraordinary deeds was the calamitous drought he imposed upon Israel for its infidelity, followed by the return of the rain, from a “little cloud like a man’s hand” (1 Kgs 18:44) which he sighted from Mount Carmel. This cloud is interpreted by many exegetes as being a pre-figure of Mary Most Holy.

It was there in that mountainous region that Elijah and his disciples began a continuous line of prophetic devotion to Our Lady, which reached its peak in the New Testament. He therefore formed “a type of bridge, from the beginning of devotion to Mary Most Holy, centuries before her birth,”5 until her last devotees, at the end of the world.

Over the years, among the followers of the Thesbite, there arose groups of hermits who represented the initial seed of the Order of Carmel. When it was transplanted to Europe in the thirteenth century, one of the first kingdoms to receive it was England, who graced the Order with one of its most illustrious members: St. Simon Stock.

Consecrated to Mary in his mother’s womb

Son of a noble family of English barons, he was born in the year 1164, in the Castle of Harford, in the earldom of Kent, of which his father was governor. Complications at birth on account of the child’s robust size raised grave concern for the life of the mother. However, the pious baroness consecrated the infant to Our Lady and he was brought into the world without further difficulty. And, “from his crib, Simon nourished a most tender devotion to the Mother of God.”6

As an act of gratitude, his mother adopted the custom of renewing her offering by praying a Hail Mary on her knees before nursing her son. Whenever she neglected to do so out of absent-mindedness, the infant would refuse to take any nourishment. It is told that he also abstained from mother’s milk on Saturdays and on the vespers of Marian feasts, and that throughout his infancy, to soothe him of any disquiet, it was only necessary to show him an image of the Virgin Mary.

Gifted with an extraordinary intelligence, he could pray the Hail Mary before completing one year of age, and he learned to read soon after beginning to speak. Early in life, following the example of his parents, he began to recite the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin, a custom that he never abandoned. By the age of six, he understood Latin, and recited the Psalms several times a day, with ardent love, kneeling out of respect for the Word of God.

Growth in knowledge and virtue

The young boy’s father, after guiding him through his first letters and sensing his inadequacy for conducting the education of such a precocious son, sent him to Oxford, where he “was wise at the age in which children begin to study.”7 Nevertheless, it was the science of the Saints that attracted Simon more than any human science, and, for this reason, his directors permitted him to receive the Sacraments at an age when “the average child is only beginning to discern between good and evil.”8

In the measure that he grew in knowledge, he also intensified his devotion to Our Lady. At the age of twelve, having read a treatise on the Immaculate Conception – seven centuries before the proclamation of the dogma! – he was seized with such ardor that, out of “desire to share some similarity with the purest of Virgins, whom he had always taken as his Mother, he consecrated his virginity to God.”9

His delicate conscience and the fear of staining his purity helped him to flee from anything that bore even the appearance of sin. And his asceticism prompted him to evade the watchful gaze of his parents to practice the penance of eating only raw herbs, vegetables and wild berries along with bread and water.

All of this provoked the virulent envy of his older brother, who led a dissolute and worldly life, in contempt of his parents’ counsels. For him, young Simon’s sanctity was an accusing finger pointed at him constantly. At first, he laid traps aimed at destroying the lad’s innocence, and then began to ridicule him for his piety. Finally, his hostility degenerated into open persecution, with calumnies and aggression.

Long period of solitude

At only twelve years of age – fearful of yielding to the allurement of the world and compelled by an interior motion of grace – Simon decided to embrace a life of solitude. He took refuge in a forest close to Oxford, where he found a giant oak whose hollowed trunk he made into his cell. A crucifix and a statue of Our Lady, the only objects he had carried with him, served to adorn this meager abode. For his daily fare, he gathered herbs, bitter roots and berries.

After a time of consolation, a new phase loomed for Simon; one of temptations and trials. The devil tormented him with scruples, fears and sharp remorse for sins that he had never committed. To overcome these attacks, he intensified his austerities and prayers, and, with the help of the Blessed Virgin, he emerged from every battle victorious. “Some authors affirm that the Angels took delight in his company, and by their presence, alleviated the harshness of his isolation.”10

Time passed by quickly! Favored by special graces, he once received a visit from Our Lady, who conveyed to him God’s satisfaction with the twenty years of solitude he had completed. Then she revealed to him that he had been chosen to enter the Order of Carmel upon its migration from the Holy Land to England, but that he would have to boldly confront the contradictions that it would meet with under his direction.

Entrance into the Order of Carmel

In order to prepare himself for this future mission, Simon returned to Oxford to complete his theological studies and receive priestly ordination. Nevertheless, God’s plans do not follow human programs; the first Carmelites would set foot on English soil only fifteen years later…

In this interim, Simon returned to his life of seclusion, and to his mounting perplexity, in 1207, the Kingdom of England fell under a devastating papal interdict. The discord between King John and Pope Innocent III concerning the nomination of the new Archbishop of Canterbury had escalated to the point that the Pontiff was obliged to take such a drastic measure.

In 1212, the first religious from Mount Carmel finally arrived. Upon receiving these glad tidings, brought to him by the Blessed Virgin herself, Simon hastened to unite himself with these Carmelites who had been appointed to instigate the foundation of monasteries on the island. But, alas, the papal interdict impeded this. The newly arrived religious withdrew to a forest in Aylesford, the property of a Carmelite friar of English origin, there to live as anchorites as they awaited more propitious days. It was at this juncture that the novice Simon received the Carmelite habit from Blessed Alain, then prior of the small community.

Becoming aware of our Saint’s rare gifts, this superior commanded him to return to Oxford and become a doctor in Theology, despite his repugnance for the worldly milieu he would be obliged to frequent. The religious obeyed, and after having obtained the title, he took advantage of a favorable opportunity to found a Carmelite hermitage in the vicinity of Norwich, thereby returning to the solitary life, along with other religious coming from Palestine.

The first obstacles to be overcome

Gradually, Our Lady’s prophecies were being fulfilled. St. Brocard, the second Carmelite superior in the West, learning of the wonders of grace being wrought among the solitaries of Norwich, especially in relation to Simon, wanted to make him his coadjutor, and, in the General Chapter of 1215, he named him as Vicar General for all of Europe, where the number of houses had quickly multiplied.

In the wake of so much good done for the Church, the father of envy unleashed a tremendous persecution against the order. Impelled by false zeal, some authorities tried to suppress it under the pretext that it contravened dictates of the Fourth Lateran Council.

Ever vigilant, Simon united all of Carmel in prayer and had recourse to Pope Honorius III. The Pontiff sent two envoys to gather information on the situation in loco, but these allowed themselves to be swayed by the opponents. The Most Blessed Virgin herself, however, came to the rescue of her sons. The Pope declared that the Queen of Heaven had ordered him to “approve the Carmelite rule, to confirm the order, and to protect it from the onslaught of its adversaries.”11 By means of the Bull Ut vivendi normam, of 1226, he put the heavenly determinations into effect and authorized new foundations in Europe.

Retreat at Mount Carmel

The hour marked by Providence had finally arrived for the Order of Carmel to leave the Holy Land and to settle in more favorable places, as Our Lady had predicted. Obeying the decision of Blessed Alain, now Superior General, Simon Stock journeyed to Mount Carmel in order to attend the General Chapter there, convoked to remedy the evils suffered in the Middle East due to the intolerance of the Saracens. The English Carmelite experienced unspeakable joy as he personally visited the prophetic mountain upon which everything had begun with Elijah.

In this Chapter, the emigration of all Carmelites to Europe was in fact determined, in spite of the objection of some of those present who said they could not in conscience abandon the few Christians left in the East. St. Simon, however, reflected that it would be futile for them to expose themselves to such a grave danger, remembering the evangelical principle: “When they persecute you in one town, flee to the next” (Mt 10:23).

As long as the Carmelites remained, the fury of the Saracens grew, and many Christians were killed in that region. Those who managed to flee to Ptolemais, where the Christian armada was concentrated, escaped death – our Saint among them.

Carmelite tradition relates that he remained for six years on the mountain of Elijah, leading a life of prayer, waiting for the opportune moment to return to his country. This arose when certain English nobles, who had fought in the Holy Land, offered the group of religious places on their homeward-bound ships. On their return, they would be divided up among the various monasteries established there. St. Simon and the Superior General went to Aylesford.

Sign of predilection and covenant with Our Lady

It was 1245 when Blessed Alain convened the first General Chapter in Europe, during which he submitted his resignation and St. Simon Stock, at the age of eighty, was unanimously elected to replace him. Under his rule the order expanded notably, especially in France, where the foundations abounded, thanks to the protection of St. Louis IX.

Even with the protection of the Holy See, Carmel was the target of new and harsh persecutions aimed at suppressing it. At the height of the affliction, the Saint gave himself up to prayers, fasting and penance; a situation which lasted for some years. It was during this period that he composed the celebrated antiphon Flos Carmeli, which he began to recite daily.

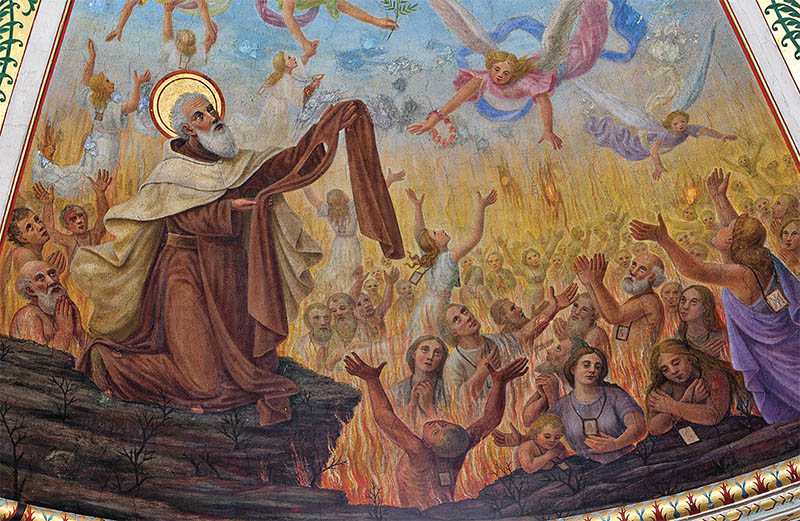

However, “in works that Our Lady loves, things can reach the point of crumbling, of shattering almost completely. Everything seems lost, but this is the moment that She reserves to intervene.”12

On July 16 of 1251, the prayer of the revered Carmelite, “like that of the prophet Elijah, opened Heaven and brought down the Queen of Angels.”13 On this date, “the Blessed Virgin appeared to him, clothed in the habit of order, crowned with shining stars, and holding her Divine Son in her arms.”14 She carried a scapular in her hands, which She gave to him as to her treasurer, in a gesture of predilection and of an everlasting covenant.

On the same day St. Simon delivered to Fr. Pierre Swayngton, his secretary and confessor, a letter addressed to all his brother Carmelites, in which he recorded the promise of the Mother of God of which he had been the depositary: “Receive, my beloved son, this scapular of your order, as a distinctive sign and the mark of the favor which I have obtained for you and for all the sons of Carmel; It is a sign of salvation, a safeguard in danger and an assurance of peace and special protection until the end of the ages. Ecce signum salutis, salus in periculis. Whoever dies clothed with this habit will be preserved from everlasting fire.”15

A long life united with Mary

From then on, the Carmelite Order spread prodigiously, and by the end of the thirteenth century, a few years after the death of the Saint, it comprised, according to sources of the time, over seven monasteries and hermitages, housing approximately one hundred and eighty thousand religious.

St. Simon Stock dedicated his remaining years to visiting the Carmelite monasteries. “Europe saw with admiration the saintly old man, in his extreme old age, bowed under the weight of years, worn down by the rigors of his austerity of life, and not diminishing his penances in the least, even during his travels, as he went with untiring courage to one after another of the monasteries of his order.”16

He journeyed to several cities of Belgium, Scotland, Ireland and other countries, until arriving in 1265 at Bordeaux, France, where on May 16 he surrendered his soul to God. His last words were the first words he had learned to pronounce: Hail Mary.

His work continues in eternity

A member of the prophetic Eliatic line, St. Simon Stock represents an isthmus between the past and the future. And since the missions of Saints do not end on this earth, the question arises: what is he doing now, from eternity? In this year commemorating the centenary of the apparitions of Fatima, is he not crying out for the coming of the Reign of Mary announced there?

Indeed, on October 13, 1917, before the famous “miracle of the sun,” The Most Holy Virgin presented herself to the three little shepherds “as Our Lady of Carmel, crowned as Queen of Heaven and earth, with the Child Jesus in her arms.”

It being proper to the spirit of the Church to love the great syntheses, it is beautiful to contemplate how, “at the moment in which Our Lady proclaims her future sovereignty in the form of the sovereignty of her Heart, she appears in the raiment of her oldest devotion, creating a synthesis between the most ancient and the most recent.” The singular figure of St. Simon Stock, Carmel and the Scapular thus announce the triumph of her Immaculate Heart! ◊

Taken from the Heralds of the Gospel magazine, #115.

Notes

1 CICERO. De oratore. L.II, n.36.

2 CLÁ DIAS, EP, João Scognamiglio. When Will Elijah Return? In: New Insights on the Gospels.. Città del Vaticano-São Paulo: LEV; Lumen Sapientiæ, 2013, v.VII, p.422.

3 Idem, p.430.

4 Idem, p.431.

5 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. São Simão Stock recebe a libré de Nossa Senhora [St. Simon Stock Receives the Livery of Our Lady]. In: Dr. Plinio. São Paulo. Ano XVII. N.194 (May, 2014); p.30.

6 GUÉRIN, Paul. Les petits bollandistes. Vies des Saints. 7.ed. Paris: Bloud et Barral, 1876, t.V, p.582.

7 Idem, p.583.

8 Idem, ibidem.

9 Idem, ibidem.

10 Idem, p.585.

11 Idem, p.588.

12 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, op. cit., p.31.

13 GUÉRIN, op. cit., p.591.

14 JANSEN, Thomaz (Ed.). São Simão Stock. In: Vida dos Santos da Ordem Carmelitana. 2.ed. Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker, 1930, p.146.

15 ST. SIMON STOCK. Letter, 16/7/1251, apud GUÉRIN, op. cit., p.592.

16 GUÉRIN, op. cit., p.593.