Calling him to found the first Order dedicated specifically to praise the Sacrament of Love, Providence wanted from him, a faith that would never allow itself to be defeated, despite contradictions and denials.

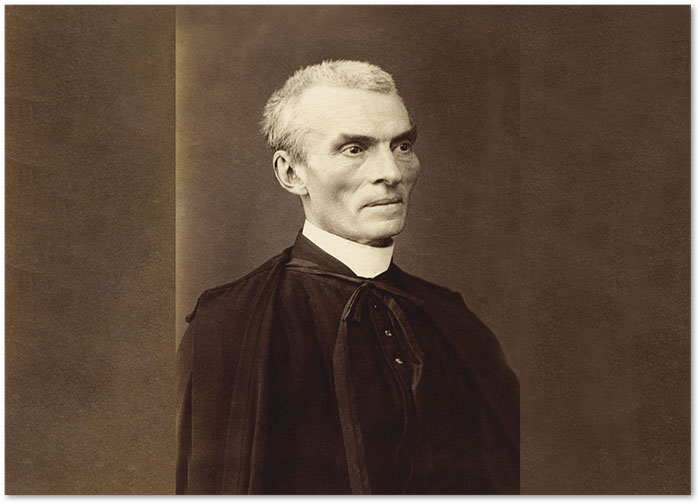

A gaunt, white-haired priest of almost sixty years, convinced that he would never reach that age due to the rigors of a life dedicated to an apostolate in which he had kept nothing for himself, converses with a devoted spiritual daughter about this earthly existence already nearing its end. The perplexity of seeing his noblest hopes repeatedly frustrated and the disappointments with which some of his closest friends persistently afflict him cause him to declare: “My consolation is that at the end of all this, there will be the Reign of the Blessed Sacrament. Oh! What thanks, yes, what thanks shall I give then.”1

* * *

In a humble house in the village of La Mure d’Isère, at the foot of the French Alps, the zealous Marie-Anne searches anxiously for her five-year-old brother, who has disappeared that morning from his mother’s sight. After going through all the rooms of the house and knowing the child’s good inclinations, it occurs to her to look in the nearby church. But neither does she find him there, until her intuition finally leads her to check behind the main altar. There, on the platform that serves as a stepping-stool for the priest in the exposition of the Blessed Sacrament, she sees the little boy kneeling with his head resting on the tabernacle. When questioned, he replies candidly that he is talking with Jesus and has chosen that particular spot: “because I can hear Him better here.”2

* * *

Five decades elapsed between this scene and the previous one. Together, however, they summarize the trajectory of a soul who, in the episode of the innocent child already indicated the orientation of his life towards God, and in the humble faith manifested on the threshold of the encounter with Him, attested to the fulfilment of his vocation amidst the contradictions of a frustrated mission. But who is it that we are describing?

Early call to the priesthood

That little boy who, in addition to attending Holy Mass daily, visited the Blessed Sacrament twice a day was called Peter Julian Eymard. With such predispositions, he soon experienced the first stirrings of a priestly vocation in his soul, promising Our Lord, on the day of his First Communion, to follow that path.

He nurtured this vocation at the feet of Our Lady, who had spoken deeply to his soul ever since, not long before, he had begun to make an annual pilgrimage to the distant shrine of Our Lady of Laus. However, the fulfilment of that calling would subject him to harsh trials, since family circumstances demanded his presence at home.

Peter Julian resolutely overcame all setbacks, especially in the struggles against himself. Years later he disclosed that these, especially in the arduous field of chastity, helped to forge his combative character, which greatly benefited the young people who knew him. Finally, at the age of twenty-three, after completing his years as a model seminarian, he received priestly ordination in Grenoble.

Fruitful ministry of a soul always called to give more

Those who analyse the life of the young priest are bound to be impressed by his excellent discharge of every duty to which his superiors assigned him.

However, from his first steps towards the priesthood, Fr. Eymard strongly aspired to the religious life, a desire which he had been unable to fulfil because of poor health and the opposition of his sister. When he met the nascent Society of Mary, the Marist Fathers, he thought he had found the fulfilment of his dream. Once again, as would be the norm in his life, there were many obstacles to overcome, but he obtained the permission of his Ordinary and entered the novitiate of the Order in Lyon.

Fr. Peter Julian’s admirable conduct caused his reputation to grow among the Marists. At the age of only thirty-three, he was appointed Father Provincial of the Order, a position immediately below that of Superior General. He also held the office of Visitor General.

The Eucharistic calling

Fr. Eymard’s future in the Congregation seemed to have no ceiling, but Providence was calling him ad maiora… In fact, although human estimation would have predicted a brilliant ecclesiastical career for him, a certain restlessness haunted his soul. Touched by a singular grace of Eucharistic devotion, he received three profound divine urgings that impelled him to deepen the intimate relationship with the Eucharistic Jesus that had characterized him since childhood.

In 1845, while carrying the monstrance with the Blessed Sacrament in the procession for Corpus Christi, he felt a powerful call to place at the feet of the Lord in the Eucharist all the needs of the Church and of the world at that time. In transports of enthusiasm, he promised to devote himself entirely to the ministry of – to paraphrase St. Paul – preaching nothing but Jesus Christ, and Jesus Christ in the Eucharist. The apostolate carried out by the Saint in Lyon in consequence of this first resolution earned him the epithet Father of the Blessed Sacrament.

But it was in 1851 that intimate mystical graces shaped in his soul the concrete character that his ministry should take, received this time at the feet of Our Lady in her shrine at Fourvière. Years later, he himself wrote of the thoughts that engulfed him then: “It is truly astonishing that, since the institution of the Church, the Holy Eucharist has not had a religious body, its guard, its court, its family, while all the other mysteries of Our Lord have had such to honour and preach them.”3 Without doubt, Divine Providence forged in Fr Eymard a certainty that would never abandon his soul: “It was necessary that there should be one.”4

Given the state of the world, it became imperative to found a congregation whose members would sanctify themselves through the Blessed Sacrament, be its permanent adorers and bring souls to the altar, reforming society on the basis of Eucharistic Adoration.

A clear vocation, ambiguously outlined

Always docile to Providence, he did not want to take any concrete action until it was clearly indicated to him. For three additional years he devoted himself to his duties with the Marists, endowing his apostolate with a profound Eucharistic character and developing various initiatives in this regard, such as the Eucharistic Days, Nocturnal Adoration and the Forty Hours.

It was only in 1853, during a filial interior dialogue while he was making his thanksgiving at Holy Mass, that Our Lord inspired him, as he later recounted, “to form an Adoration that was perpetual and for everyone,” asking for “an absolute sacrifice, that everything be immolated,” including his life in the Marist Congregation. He accepted the invitation ipso facto and was “overwhelmed with consolation and also with strength,”5 which never left him, to withstand all that this commitment entailed.

The Lord called to him from the Sacred Host that rested within him: “Gather to Me my faithful ones, who made a covenant with Me by sacrifice!” (Ps 50:5). However, his insatiably passionate heart was not content with founding a work that would provide the greatest splendor, as never before, for the worship of the Blessed Sacrament. This was only the starting point. His aspiration was to lead all peoples to Him, and in this way reform a society that was heading for complete ruin: “I would still like to do great things for God before I die. […] I ask God, if there is no pride in this, to grant me a mission that will lead me to do good throughout the whole earth.”6

This strong motion of grace was quite daring for the time and circumstances in which he lived. From his comprehensive purview, the Saint clearly saw what this meant, but he did not shrink back or hesitate to press ahead: “I promised God that nothing would stop me […]. Above all, I asked […] for the grace to apply myself to this work without human consolations.”7

A founding strewn with obstacles and failures

Fr. Eymard would take the initial steps towards the longed-for foundation with a retired naval officer, Count Raymond de Cuers, a recent convert who would later become a priest and be his first disciple. To carry it out, however, he had to obtain dispensation from his religious vows in the Society of Mary, where he encountered very strong opposition which cost him great suffering. Many of those whom he still considered his brothers in the community regarded him as a traitor to the vocation, for, they said, he was abandoning the congregation to launch himself into a merely human project, driven by a desire for personal fulfilment.

Having finally obtained permission, the two companions set out to accomplish the work to which they aspired, with the blessing of Pope Pius IX, who encouraged their undertaking, and of the Archbishop of Paris. However, their lack of means was such that they often feared for the continuity of their foundation, for they were even evicted from the first house where they gathered. For years on end, they were unable to find a suitable house or a place in which to build the dignified throne they desired for Our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament.

This would have been nothing if vocations had been attracted to the new project… But the scarcity was distressing, for the first candidates capitulated before the privations to which circumstances subjected them, thus preventing the establishment of regular adoration of the Blessed Sacrament.

Worse still, harsh criticism of the nascent work was not long in coming; among the critics were numerous ecclesiastics. Many of them, oh, sorrow, came from his former fellow Marists, who accused him of sowing tares in the Lord’s field with the foundation.

Finally, came what was perhaps the most painful trial: some thought that all these setbacks, which only increased with the passing of the years, indicated that the work did not have Heaven’s blessings. This instilled in the first followers of Fr. Eymard a strong distrust of his role as founder, creating a lamentable void around him. This indisposition was especially felt by the one he considered a true brother, Fr. de Cuers, who had accompanied him from the beginning and was now increasingly jealous of him, wanting to appropriate something of the foundational grace that was not his. Finally, under the ridiculous pretence of a more radical dedication to the Blessed Sacrament than that of the Saint, he even separated from him to found his own Eucharistic Order. The incomprehension and comparison of the one who should have been his greatest support, and who even dragged others along behind him, was one of the greatest sufferings that St. Peter Julian had to endure. Nevertheless, with heroic resignation, he never denied his support and friendship to his old companion.

In the midst of so many obstacles, the work forged ahead. We can understand, however, how far these conquests were from the splendid horizon that had captivated the founder years before. Providence denied him, according to his request, any human consolation. Was He, however, condemning to failure one who had been such a remarkably successful priest? According to human criteria, perhaps, but from the divine viewpoint, the reality was quite different.

The path of perplexity, guarantee of supernatural success

There is something that causes more suffering to the human heart than any physical pain: contradiction. When the Lord asked Abraham to sacrifice the son of the promise, the patriarch’s heart groaned because God’s demand contradicted what He Himself had promised.

Why does the Most High do this? He granted man reason so that, in knowing Him, he might love Him. Nevertheless, on certain occasions He demands of His creature such a high degree of surrender that it surpasses the limits of understanding. He asks him to make strides in vast panoramas of faith, but without providing any explanation. Such a demand is presented as a contradiction, or even as a veritable absurdity, before which the poor human intellect feels tiny and powerless.

This was exactly the situation in which Fr. Eymard found himself. In making explicit, by a profound divine inspiration, the sacramental call, he had prophetically contemplated to what pinnacles of love for the Blessed Sacrament his work was to lead the Church and the world, to the point of a complete transformation of society. However, as the years passed, he realized how far the Congregation and the majority of his spiritual sons were from the realization of what the Lord had spoken to him interiorly, to the point that, seeing the end of his life approaching, he confided to them: “I will die, and when I am no longer here, no one will have the grace of the foundation… […] Therefore, take advantage to ask me and to make greater use of me. I speak to you as much as I can, but you are content to listen to me and let it pass…”8

Those whom God chooses to tread the paths of contradiction have only two options: either to rebel, abandoning their first love and joining those who in Heaven cried “Non serviam”; or to submit, even amid the fog of incomprehension, joining the myriad who cried “Quis ut Deus” and persevered in their fidelity to the One who loved them first. St. Peter Julian Eymard chose to follow the path opened by St. Michael and his Angels.

Corpus Christi procession at the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary, Caieiras (Brazil)

Final trial and consolation amidst seeming denial

During his life he did nothing but fight, pray and sacrifice himself for the founding of a Eucharistic Kingdom among men: “May the Reign of Thy love come and spread over the whole earth, consuming it with a heavenly and eternal fire.”9 And the denial of seeing the fulfillment of this ideal, the more distant the more he personally strove for it, was undoubtedly a trial to which God subjected him for a very high reason unknown to him. This is the great perplexity of the founders: to contemplate the possibility of establishing a reflection of Heaven in this world, but not to see its complete realization. Nevertheless, in reality, more than their human contributions to the realization of this dream, the Almighty Lord wants from them the perfect oblation of a faith which, despite contradictions, never allows itself to be defeated.

Was there any mystical consolation that sustained the Saint at the end of his days? We are told, for example, of the mysterious apparition in his room of a nimbus, in which his devoted assistant, not particularly inclined to believe such things, was able to see the delicate folds of a garment. Was it Our Lady warning him of his imminent departure and consoling him in this vision? We shall never know for sure. But we can infer that, sustained by faith, he had such a full assurance of the fulfilment of his mission, that a few days before his death, he affirmed, as we saw at the beginning of this article: “At the end of all this, there will be the Reign of the Blessed Sacrament.”

Whether before or after his passage into eternity, St. Peter Julian Eymard beheld the effect of this holocaust of confidence, consummated with heroism: the monstrance, surrounded with the greatest honour, reigning over a society made up of holiness. His efforts to establish this Eucharistic Kingdom were not in vain. He understood that it was necessary for someone to suffer with a clear understanding of the goal of his anguish: that one man believe in the fullness of such a Kingdom without seeing it in this life, so that others could contemplate its full realization. The founder of the Sacramentines did this to perfection, making a decisive contribution to the triumph of the Immaculate Heart of Mary announced half a century later to the world at Fatima; for the Reign of Our Lady and the Eucharistic Reign are but one. ◊

Taken from the Heralds of the Gospel magazine, #178.

1 BLESSED PETER JULIAN EYMARD. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Eucarística, 1953, p.593. The biographical information for this article was also taken from this work.

2 Idem, p.8.

3 Idem, p.175.

4 Idem, ibidem.

5 Idem, p.255.

6 Idem, p.262.

7 Idem, p.256.

8 Idem, p.609-610.

9 Idem, p.351.