Contemplating the gradual fading of the lights of Christian Civilization, in which its bastions were systematically attacked and left in ruins until almost nothing remained of them, the Catholic soul kneels before this rubble, once surrounded by splendour and promise, and its love seems to ask of those now lacklustre stones: how was it possible to arrive at such desolation?

Then, looking back on the past, it seeks the answer to its perplexity in the course of events.

Martin Luther stands as the protagonist of the First Revolution. But was he really the first “Protestant”? We have already seen that he was not. Similar confrontations with the Holy See had already taken place in previous centuries. So how is it that the Augustinian friar tore Christendom apart, taking a third of it with him, when he declared his break with the Church?

We may wonder something similar about the Second Revolution. The first-born daughter of the Church lies decapitated. The king was the head of society; he was cruelly murdered and his figure torn from the souls of his subjects. Now, did the follies of the nobility and the penury of the peasants, which were alleged for the insurrection in 18th century France, form an unprecedented situation in the country? What led those people to drag themselves into such a shameful state, when their ancestors had valiantly overcome worse vicissitudes?

We could repeat this observation with the Third Revolution and other historical episodes in which the revolutionary fury attained important goals.

What detonated these explosions at the precise time they occurred, and not in previous centuries when similar ideas and situations also arose? We must recognize that there was a prior preparation that made them successful. To explain this phenomenon, Dr. Plinio often used the following metaphor.

Imagine a person who goes to the organization responsible for preserving a lush, verdant forest to explain his plans to burn it down. The director would reply nonchalantly: “Every day the train passes by shooting out its sparks and the vegetation has never caught fire! You will not be able to do such a barbaric thing with your match!” The criminal would listen quietly.

For nights afterwards, however, he would have men inject those trees with a mysterious substance that would make them dry up completely. One day, with the same match with which he had taunted the director, he would light the fire; in no time at all, the whole forest would be ablaze. What had previously resisted the sparks became combustible.

Although eloquent in itself, the metaphor needs to be explained. Indeed, if the “forest” symbolizes Christian civilization, made up of countless trees of virtues, customs and holy institutions, what do the “mysterious injections” correspond to? This point is fundamental to understanding the problem…

Dr. Plinio discovered this early on, when he witnessed one of these “injections” while yet in childhood.

At school, two worlds collide

A whistle sounded in the courtyard and, as if that sharp, prolonged sound had detonated it, an explosion followed. Overexcited boys, sweating from agitation, ran everywhere, shouting in complete disorder. On the fringes of the confusion, a young boy watched on. It was his first day at school.

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, who was ten years old at the time, had grown up in a home with deep traditional roots, where education and composure translated into distinction in behaviour and faith bathed the first steps of his life in a golden, supernatural light.

“Accustomed to this upbringing, I entered school as if a meteor had abruptly thrown me – from within this cosy, quiet and traditional environment – thirty years forward and headlong into the brutish mare magnum of the Revolution,”1 he would later comment.

It was not a matter of mere childish shock as a result of immaturity faced with the unknown; it was a clash of good and evil, of order and disorder, of little Plinio who, living in the “earthly paradise” of innocence, heard the first roars of the Revolution.

In those first encounters, however, he was presented with the winds of novelty, apparently as exciting as they were harmless, and only a fine discernment would be able to recognize their evil.

Plinio at St. Louis College in the year 1921

In fact, young Plinio began to observe how, among young people his age, brutality had replaced ceremony, and respect had given way to an unscrupulous intimacy: they slapped each other on the back, exchanged offensive sarcasm and jokes; in language, indecent words had entered everyday vocabulary, exerting a special attraction; in dress, decorum had became old-fashioned, and a more relaxed and informal style was imposed.

On the other hand, if the home environment encouraged him to develop all the healthy aspects of his personality, at school, in the opposite direction, there was a pressure that led everyone to adhere to the same state of mind and revolutionary ways, in an intense action of massification.

Radical changes take hold in society

With the end of the First World War, these changes became even clearer. Coming out of that tragedy exhausted, humanity craved well-being, spontaneity and pleasure, and threw itself eagerly onto the path of novelty.

In this context, the cinema played a decisive role in providing something more than distraction or leisure, as Dr. Plinio observed: “I noticed that the cinema had a tendential effect on everyone, shaping their temperament, their customs, their way of being and thinking, in short, transforming their existence. It was the great vehicle of progress and of the Revolution.”2

Comedy films introduced a certain way of laughing, telling jokes and having fun, just as crime dramas created a state of soul intoxicated with excitement, tension and a fever for speed, which seemed to want to maximize the human capacity for sensation.3 However, it was not just any pleasure that was encouraged: those of the spirit were out of vogue.

In this new consideration of human life and activities, God no longer had a place: a kind of earthly and materialistic “heaven” was sought, guaranteed to those who possessed health, money and good fortune. And so the concept of evil came to be identified with suffering or pain, the elimination of which was always a good.

Little by little, the innovations crossed the boundaries of mere sentiment and invaded the field of ideas and facts. Dr. Plinio was by then a grown man and ready to wage his heroic struggle in defence of the Church and Christian civilization. However, the initial phase of his confrontation with the Revolution would always remain a fertile ground of inspiration for understanding how it worked to fulfil its designs.

Disorder in the human spirit

Describing the revolutionary process in mentalities, so subtly carried out by sometimes unsuspected means and with messages contrary to morality and Religion, we arrive at its deepest – and perhaps the most important – field of action as Dr. Plinio described it: “We may also distinguish in the Revolution three depths, which chronologically overlap each other to some extent. The first of them, which is the deepest, consists of a crisis in the tendencies.”4

Before Adam’s sin, human tendencies – originating from the senses of the soul and body – were in complete order: “Owing to original justice, the reason had perfect control over the inferior parts of the soul, while reason itself found its perfection in submission to God.”5 As long as our first parents were docile to God, their spiritual side would predominate over the animal side: they would turn naturally to the things of the spirit more than to the things of the flesh. This disposition governed every aspect of life in Eden, even in commonplace things, as Dr. Plinio explained to his young audience:

“Looking at anything in Paradise, or simply sensing it, man knew how to turn his soul above all to God, the Creator of everything. In the heat and the cool breeze, he knew how to see Divine Providence. He was not detained in the delight – like someone at a seaside resort today, opening his arms and trying to catch the wind – but thought: ‘How the heat of the day reminds me of the power of God! How the cool breeze reminds me of the wisdom with which He limits His own power, so that His presence does not become excessive for man whom He loves.’ And he received everything as a gift and a caress from God.”6

Eva e a Serpente – Eve and the Serpent – Cathedral of Rheims (France)

Adam, however, expelled this paradise from his soul. With his sin, the perfect balance that inhabited him was broken: his intelligence was dulled; his will was hardened towards the good, becoming weak and indecisive, and acting correctly became difficult; concupiscence, previously regulated by temperance, became overly inflamed7 and it began, contrary to the principles of reason, to seek satiety in earthly goods.

For the heirs of original guilt, even in those who have been bathed in the waters of Baptism, its effects remain. For this reason, the corruption of sensuality – in its broad meaning, as identified by St. Thomas Aquinas with the sensitive appetite – by which we are inclined to sin – never completely disappears in this life,8 so that practising good by curbing this propensity is the great struggle of life.

The Revolution, in turn, strives to exacerbate this human weakness, for the success of its machinations depends on it.

The dynamism of the process lies in the tendencies

St. Thomas9 explains that while reason is particularly important in good, in evil, on the other hand, it is the lower part of the soul that comes first.

Therefore, the aim of the Revolution in this first stage is to put all the tendencies in disorder. “What does this mean? It means instituting complete intemperance in the human spirit, for more and for less. So that, for example, on occasions when there is a reason for a person to feel thing ‘x’, they feel ‘y’; when there is an occasion to feel ‘y’, they feel ‘z’ or feel nothing at all. And, as a corollary of intemperance, to institute a total disorder in the world of sensation.”10

In general, such disorder will replace Heaven with pleasure as the goal of life. Depending on psychology, character or upbringing, the manifestations of intemperance will take on each person’s own characteristics. For example, there will be those who desire intense and noisy sensations; more mediocre or more refined mentalities will be content with little pleasures, preferring to savour life in little teaspoons.

For everyone, in the final analysis, what makes up a life of pleasure? First and foremost, in carefree enjoyment that delights the body, directly and immediately. Secondly, in doing whatever one wants – one’s wish is the law! Unbridled tendencies gradually lead to the abolition of all restraints imposed by morality and good manners; and man, proclaiming himself free, becomes a slave to his passions.

The means to affect human tendencies

Once the bad propensities of the generality of individuals have been exacerbated, the Revolution will be in a position to take the next planned steps: “These disorderly tendencies which, by their very nature, struggle for realization, no longer conforming themselves to an entire order of things contrary to them, begin to modify mentalities, ways of being, artistic expressions, and customs without immediately touching directly – at least habitually – on ideas.”11

Once the field has been prepared by this process, doctrines will later find good ground to take form as explicit ideas. Only then will the Revolution be ready to reach the “the terrain of facts, where it begins to work, by bloody or unbloody means, on the transformation of institutions, laws, and customs, whether in the religious realm or in temporal society.”12

The success of the great revolutionary upheavals, therefore, will always be the consequence of a preparation, first tendential and then sophistical. Dr. Plinio exemplifies this reality with the gunpowder that acts as the fuse before the fireworks explode. In order for the explosion to occur, there must have been this “path” beforehand.

One of the innumerable historical cases that illustrate this principle is the statement by a certain Spanish public figure who, in the midst of the de-Christianizing march of that Iberian nation, said that it was necessary to put an end to the taboo of virginity in order to abolish the right to property.

It should also be noted that this process does not take place overtly, but rather cunningly and discreetly, because the less it is noticed, the more likely it is not to encounter resistance. In fact, the Revolution only progresses “by concealing its complete form, its true spirit, and its ultimate aims.”13

An archetypal example is the Renaissance and Humanism, which, as we have seen, paved the way for the outbreak of the Protestant pseudo-reformation. Sculptures that were perfect from an artistic point of view, representing human strength and excellence, admired indiscriminately, sowed the seeds in humanity of the idea – still widespread – that the era in which man depended on God, as depicted in medieval paintings, was outdated. If anyone were to say this, they would undoubtedly be admonished by the whole of Christendom. But the arts proclaimed it, and everyone went along with it.

Already dominated by the fascination of a neo-pagan and often frankly indecent art, souls easily bought into moral degradation in the facts.

One could cite examples in all areas of culture over the centuries, to the point of exhaustion. The reader will notice that every great ideological or social explosion has always been preceded by a cultural revolution, and this is no mere coincidence.

A vicious circle is thus established which – barring the merciful intervention of Providence – nothing can stop: the tendential Revolution launches man into intemperance; his bad inclinations are both catered to and stimulated, demanding more; a new innovation is offered to him. In short, “errors beget errors, and revolutions open the way for other revolutions.”14

The tendential aspect of today’s fight

Until the beginning of the last century, the Revolution used the tendential “weapon” as a remote preparation for the breaking of a principle. Nowadays, however, it has practically ceased to act in the ideological field, or at least devotes much less emphasis to it, focussing its efforts on the different facets of what is called “cultural revolution”.

Has its century-long experience taught it that it is enough to stir the passions in order to win, or is the disintegration of the human soul already so advanced that its iniquitous work is much easier?

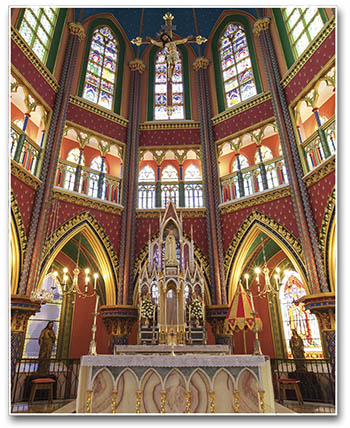

Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Fatima, Cotia (Brazil)

Not by chance, Dr. Plinio observed in the third part of Revolution and Counter-Revolution, written in 1976, the importance that the tendential revolutionary aspect had acquired and that, therefore, it was necessary to “prepare to fight, not only by alerting people to this preponderance of the tendencies – fundamentally subversive of good human order – that is on the increase, but also using all legitimate and appropriate means in the tendential field to combat this same revolution in the tendencies.”15

And we can safely say that in the last half-century, this pre-eminence has only grown… To those, therefore, who do not want to be swept away by it, Dr. Plinio points out only one solution: “The fear of losing the state of grace puts us in an incessant fight, at all times, and this fight begins with discernment and vigilance.”16

May Our Lady grant all counter-revolutionaries the sagacity and perspicacity to remain resistant to this enemy that surrounds us even in the least aspects of daily life. ◊

Taken from the Heralds of the Gospel magazine, #195.

Notes

1 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Notas Autobiográficas [Autobiographical Notes]. São Paulo: Retornarei, 2010, v.II, p.40-41.

2 Idem, p.89.

3 Cf. Idem, p.94-103.

4 RCR, P.I, c.5, 1.

5 ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Summa Theologiae. I-II, q.85, a.3.

6 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Conference. São Paulo, 9/11/1984.

7 Cf. ST. THOMAS AQUINAS, op. cit., q.82, a.3.

8 Cf. Idem, q.74, a.3, ad 2.

9 Cf. Idem, q.82, a.3, ad 3.

10 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo: 8/8/1993.

11 RCR, P.I, c.5, 1.

12 Idem, 3.

13 Idem, P.II, c.5, 3, A.

14 Idem, P.I, c.6, 3.

15 Idem, P.III, c.3, 3.

16 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Conference. São Paulo, 9/11/1984.