Thomas was born in Aquino at the end of 1224 or the beginning of the following year into one of the most illustrious families of the Kingdom of Sicily. His relatives included the Emperor Redbeard, his uncle, and Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire, his cousin.

Hoping to see one of their offspring occupying the abbatial throne of the monastery of Monte Cassino, located in the immediate vicinity of the family fief, his parents arranged for little Thomas to enter religious life. Barely six years old, he was already following the path of the great St. Benedict. Possessed of a spirit at once profound and elevated, he reflected on the truths of the Faith that he heard. Even at the beginning of his education, he was known to ask his confreres for a full explanation of who God was.

Contact with the Order of Preachers

Owing to certain disputes between the Holy Empire and Rome, his parents sent him to Naples when he was 14 to study the liberal arts at the university that had just been established there. It was during this period that his true vocation blossomed. When he came into contact with the Order of Preachers, recently founded by St. Dominic de Guzman, he was greatly attracted and joined its ranks.

However, being mendicant, the Order clashed with the worldly standards of the time, especially with his parents’ objectives for human realization. His mother therefore ordered his siblings to kidnap Thomas and bring him back home.

Teacher in Paris

With his home imprisonment behind him in 1245, the young religious was led by the Superior General of the Dominicans himself to the capital of Christian thought: Paris, the “new Athens”. It was in Saint-Jacques Monastery that he found the atmosphere of recollection and meditation necessary for the proper pursuit of his studies. To study theology he entered the university, where he had the Seraphic Doctor, St. Bonaventure as a companion, and as guide and master St. Albert the Great, the Universal Doctor, whom he followed three years later to Cologne.

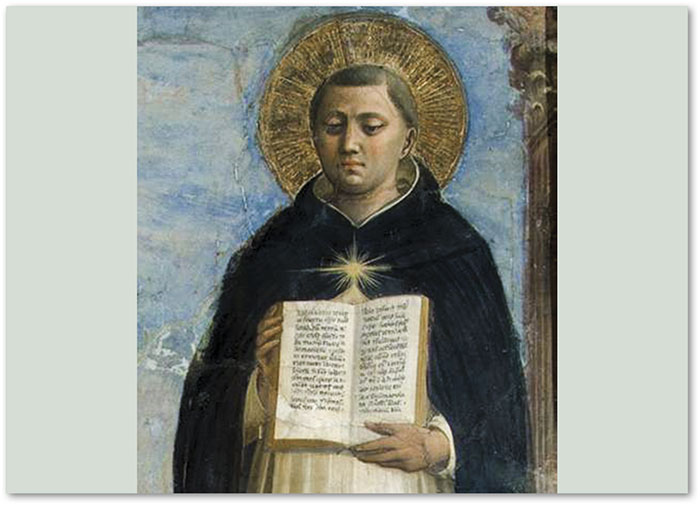

St. Thomas Aquinas, by Fra Angelico – National Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (Russia)

Having completed his baccalaureate, he returned in 1252 to Paris at the age of twenty-seven and began teaching in order to obtain a master’s degree. In March 1256 he received the licentia docendi together with St. Bonaventure. During this period he wrote commentaries on Peter Lombard’s Sentences, as well as on the Gospel of Matthew and the Book of Isaiah. Four years later he wrote the Summa contra Gentiles, a work in which the philosophical principles that support the Christian faith are discussed.

His reputation as a scholar and Saint reached the highest ecclesiastical circles. Between 1259 and 1268, he was summoned to accompany the Papal Court on journeys through Italy as a theologian-consultant to the Pope. He reconciled his new task with his teaching duties in Paris.

Ardent devotee of the Blessed Sacrament

Thomas had such great love for the Bread of Angels that he was wont to awake at night and prostrate himself before the tabernacle. When the bell rang for Matins, he would return secretly to his cell so that no one would notice him. Divine Providence, however, arranged events in such a way as to make manifest to the world the Eucharistic ardour that overflowed from the heart of this great man.

It is said that Urban IV, in order to create a proper office for the newly instituted Solemnity of Corpus Christi, asked each of his principal theologians to prepare a proposal, so that the most suitable one could be chosen. When the deadline arrived, they all met with the Pope and, not without reluctance, St. Thomas was the first to read his own work. Hearing the praises flowing from the heart of Aquinas caused a general stir. St. Bonaventure, who was also present, was so impressed by the content of the Angelic Doctor’s composition that he tore up his compositions, and the others followed suit. It was an attitude of unusual humility, unfortunately so rare in intellectual circles…

From the sequence Lauda Sion, whose praises will always fall short of its deserts, seems to rise up to Heaven the purest and most devout clamour of those who find in the Sacrament of the Altar the Real Presence of that same Jesus who, triumphant, walked through Galilee after the Resurrection to encourage His Apostles.

Counselor of the King

Having returned to Paris in 1269, he was appointed by St. Louis IX as his personal advisor.

The holy monarch once invited him to a meal at his table. Without giving the least thought to the prestige that such an invitation implied, he declined on the grounds that he was dictating the Summa Theologica, a work that could not easily be interrupted. The king then turned to the Saint’s superior, who in the name of obedience ordered him to attend.

While the diners were engaged in lively conversation, Father Thomas remained aloof, immersed in his cogitations. The courtiers, amused and intrigued, watched their peculiar fellow-guest, who suddenly struck the table, exclaiming in a loud voice, “Modo conclusum est contra hæresim Manichæi!”1 He had just found the decisive argument against the heresy of the Manichaeans, and could not contain himself for joy. Stupefied, the superior rebuked him, reminding him that he was in the presence of the king and the nobility. However, St. Louis, who shared the same ideals for the triumph of truth and the service of God, ordered his personal secretary to take note of the newly formulated argument.

A mysterious vision

Two years before his death, obedience took him back to his homeland in order to found a great Dominican theological center there, like the one in Rome. In the little time he had left, he devoted himself to writing the third part of the Summa Theologica, which was ultimately left incomplete…

After the feast of St. Nicholas, Reginald of Piperno, his faithful secretary, noticed that Thomas had stopped writing and was more silent than usual. So he asked him the reason for such an attitude. “I cannot continue,” replied the master. After much insistence on Reginald’s part, he finally stated, with a request for confidentiality: “Everything I have written up to now seems to me as straw compared with what I have seen and what has been revealed to me.”

“I leave everything to the correction of Holy Church”

A few months later, Pope Gregory X called an ecumenical council in Lyon, in which the Angelic Doctor was to take part. The latter, ever more focused on supernatural realities and detached from the world, was detained in the middle of the journey by a mortal illness.

His words after receiving viaticum are worthy of note: “I receive Thee, pledge of the ransom of my soul, I receive Thee, viaticum of my pilgrimage. For love of Thee, I have studied, I have watched, I have laboured; Thee have I preached and taught. I have said nothing against Thee, but if I have, it was unknowingly; I do not obstinately persist in my judgements; if I have written erroneously regarding this or the other Sacraments, I leave everything to the correction of the Holy Roman Church, in whose obedience I now leave this world.”2

On March 7, 1274, having devoutly received the last Sacraments, he surrendered his soul. And finally he was able to contemplate without veils the One whom from childhood he had sought to know and love, and of whose cause he had made his future. ◊

Taken from the Heralds of the Gospel magazine, #189.

Notes

1 From the Latin: “Thus the refutation against the heresy of the Manichaeans is complete!” (WILLIAM DE TOCCO. Ystoria Sancti Thome de Aquino, c.43. Toronto: PIMS, 1996, p.174-175).

2 AMEAL, João. São Tomás de Aquino. Iniciação ao estudo da sua figura e da sua obra. 3.ed. Porto: Tavares Martins, 1947, p.154.